Development strategy and tool stack

Author: Currently, David Orme but intended to be collaborative.

This document describes the key development tools and principles for the project. It includes suggestions made by the Research Software Engineering team in their proposal for some key tools.

This document will likely move into our project documentation at some point!

Python environment

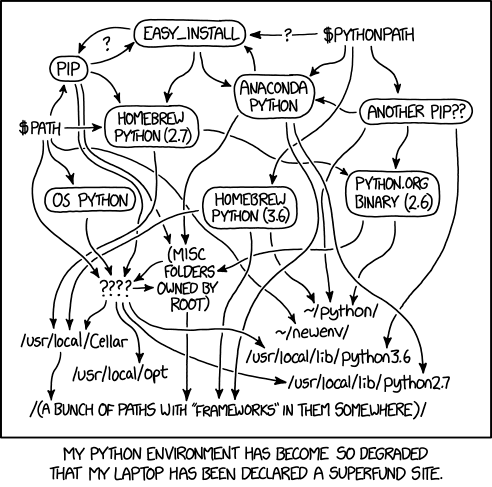

Python is notorious for having many versions of key components and it is common to end up with multiple versions installed on single computers.

Unless we manage this up front, we will end up with problems from inconsistent versions. So:

We will be using Python 3 and probably a minimum version of that. At the moment, I’m thinking 3.7+ for

dataclasses, but maybe even 3.9+ for some advances in static typing.We will use

pyenvto maintain python environments. This allows us to keep multiple versions of Python in parallel and switch between them cleanly: we will want to be able to run code on different Python versions.RSE have suggested we use

poetryas our tool for package installation and management. I have not used this but it would replacepiporcondaand looks to provide a really streamlined way to manage dependencies and package publication.

Interactive development environment (IDE)

This is not so critical, but it might make sense to use the same IDE programs (and plugins) for code development. I’ve used PyCharm a fair bit but more recently have been using Visual Studio Code. Both are free - PyCharm via an academic licensing program - PyCharm has greater complexity but I have sometimes found it a bit slow and finicky to use.

Code versioning platform and strategy

We will be using GitHub as our repository for package code and documentation. We will be using the Git Flow strategy for managing code development cycles.

The idea behind GitFlow is to separate out code development and release into a clear

branching structure, so that different branches are used for different purposes rather

than everything happening on a single trunk branch.

I’ve used this on several projects, mostly for the idea of release cycles, and I like it a lot. I have basically used three branches from the GitFlow concept:

develop: This is the branch on which code development occurs.release/x.y.z: These are temporary branches that are used to take a particular commit fromdevelopand make it available as a new release. The temporary branch is used to separate out all the usual building and checking and to allow review.master: You do not work on themasterbranch. When areleaseversion is good to go, then that branch and any commits on it are pushed ontomaster, essentially creating one big bundle of commits that movemasterfrom the code in versionx.y.ztox.y.z+1. The commits inreleaseare also copied back intodevelopso that it also contains the same code.

However, GitFlow also uses feature branches - which are intended to separate the

introduction of sizeable new features from develop until they are in a fairly complete

state. I have not used this much and there has been some criticism of the level of

branching and merging that can result.

Using GitFlow is made easier by git extensions that

condense the commands for particular steps.

Continuous integration

We will be using continuous integration (CI) to develop the code. This is a process where changes to the code in the repository trigger automatic processes to build and check the code. It is essentially an early warning system: if we make commits that break some of our working practices then the CI platform emails people to say it is broken.

The CI process can be used for all sorts of checking (see below for more on these topics):

Unit testing: does our code still return the same expected values and behaviour?

Code quality: does it pass linting and have decent code coverage?

Documentation building: does the documentation all compile correctly?

I have previously used Travis CI for this but they have just moved away from free support for open source projects. RSE have suggested Github Actions, and having just moved one project to that, it seems like a straightforward replacement.

Unit testing

We will be using the pytest framework for unit testing. I have used this quite a bit

and it is also the RSE recommendation.

A unit test is a function that does something using the code and then contains a set of assertions about what the result of running the code should be. There are a wide range of assertions, such as that:

adding_function(5, 2)does indeed return7,adding_function(5, 'a')throws aValueError,do_this_thing(verbose=True)emits the correct logging message (INFO: I did a thing).

The pytest framework is very extendable:

Fixtures are things that can be shared between tests: one might contain the code for loading a configuration file and returning the

configobject, rather than duplicating that code in each test needing a configuration.Tests can be paramaterised: a test function can be wrapped in a decorator that provides multiple inputs and outputs, allowing the same test to check multiple use cases without duplicating code.

Fake file systems can be created: ensuring that particular file resources appear in predictable places, so that tests do not fail because of local file paths.

We will also likely make use of the doctest framework. This framework looks for

instances of runnable code in examples in code documentation and checks that the values

created by that code and reported in the documentation agree. The pytest framework

does the main job of checking code, but doctest additionally makes sure examples in

documentation are correct.

I would also add to this using a code coverage checker. I have not used one of these before but the idea is that, when unit testing is run, this tool records which parts of the code are used in the testing and identifies lines of code that are not run in any testing.

Code and documentation styling

We need to adopt common practices for writing code and documentation. There are lots of aspects to this:

Coding style: I suggest we adopt the Google coding style for Python. This is pretty wide ranging and include code layout, best practice for some use cases and how documentation within the code (

docstrings) should be structured.Autoformatting: RSE have suggested we use

blackas an automatic code formatter. I’ve never used a tool like this but the idea is to automatically enforce a particular style - the code file is transformed byblackto meet the coding style. This makes it easier to avoid code style problems before code is committed to the repository.Linting: A linter is an tool that automatically checks whether a codefile conforms to a particular code style. I have previously used

pylintbut RSE have suggested we useflake8, which helpfully supports the Google code style. This tool can be run locally, but it is also likely to be part of the CI suite of actions, to highlight when we have problems with bad style.Type checking: RSE have suggested we use mypy for static type checking, which I have not used before.

The issue here is that Python code is often dynamically typed: the code does not specify the

typeof inputs or outputs of code. Since Python 3.0 - and with increasing detail in more recent versions - it is now possible to add explicit annotation to Python code that indicates the accepted types of inputs and the type of outputs. A tool likemypyautomatically checks that an input of a given type is used in ways that make sense:def my_func(x: int) -> int: val = 'value: ' + x return val

This will fail - it attempts string concatenation on something that is expected to be an integer and then returns a string while claiming to return an integer.

Documentation

There will be documentation. Lots of documentation. There are three components here that we need to address:

the approach we use to actually writing and structuring documentation content,

the framework used to deploy documentation from source files,

where we actually host documentation so that people can find and read it.

Content guidance

RSE have pointed us towards the Diátaxis framework which provides a useful breakdown of four distinct documentation modes (tutorial, how-to, explanation and reference) and how to approach these with users in mind. This is primarily about how to write the content.

The documentation framework

The idea here is to write content in a quick and easy markup language and then let a documentation framework handle converting it all to HTML. We want to handle docuementation two broad file types:

Reference documentation: we will be using docstrings to provide the reference documentation for the code objects and structure. These are marked up descriptions of what code does that are included right in the code source. Doing this keeps the explanation of the code close to the code itself, making it easier for developers to understand how the code behaves.

Documentation frameworks can extract the docstrings from the code and automatically create structured HTML files to provide a code reference.

def my_function(x: float) -> float: """ This is a docstring that describes what `my_function` does. Args: x: A number to be doubled Returns: A value twice the value of `x` """ return 2 * x

Everything else: this covers how tos, tutorials and explanation. These will be written in simple markup files, using a framework to convert the markup into HTML. However, for many of these files we will want dynamic content: this is typically going to be code that is run within the content show how to use the code or generate figures etc.

There are a lot of frameworks around and things are moving fast in this area. The classic option for a Python project is Sphinx but mkdocs is also becomign popular. There is also the whole development of Jupyterbook.

RSE have recommended Sphinx: it is incredibly mature and feature rich, but that depth

can get a bit confusing. mkdocs is a bit lighter and faster and has a very nice live

preview system, but has a less mature automatic reference documentation system.

Some notes:

Both of these will support dynamic content generation by running

jupyternotebooks before conversion to HTML.We have a choice of markup languages.

RSTis the traditional choice for Sphinx butmkdocsuse Markdown. I find Markdown cleaner and the recent Markdown extensionMySTgives it a similar functionality to RST.One minor issue here at the moment is that although Sphinx supports MyST for standalone files it cannot currently be used in docstrings, leading to a mixed use of RST and MyST. That is an area under active development though.

I don’t think the exact details are nailed down yet but I think we should start with Sphinx and MyST and be ready to adopt MyST in docstrings.

The documentation host site

There are no end of places to host static HTML. You can create a website by just putting the content in an Amazon S3 bucket. GitHub has GitHub Pages, which runs a website from the content of a named branch in the same repo as the code.

RSE have recommended ReadTheDocs. I’ve used this a lot and it is very good: it maintains versions of the documentation and builds the documentation from scratch whenever code is updated. It is supported by adverts, but they aren’t very intrusive.

I do have to say that I find it slightly fussy to have to watch and trouble shoot the remote documentation building as part of the release cycle. It is in some ways easier to build the docs locally and simply update the host with changes. However, that is very much in single code projects, and having a remote building process is a bit like having Continuous Integration for the documentation.

Having said that: switching host is not a big deal, at least in the early stages of the project!